Introduction

Random walk models are fundamental stochastic processes widely used in time series analysis, spatial statistics, and Bayesian smoothing applications. They provide a flexible framework for modeling data where consecutive observations are correlated and the underlying trend varies smoothly over time or space.

The random walk models in ngme2 extend

traditional implementations by allowing for non-Gaussian noise,

particularly the Normal Inverse Gaussian (NIG) and Generalized

Asymmetric Laplace (GAL) distributions. This flexibility enables

modeling of data with asymmetric behavior, heavy tails, and complex

dependence structures commonly observed in real-world applications.

This vignette provides a comprehensive guide to implementing and

using random walk models within the ngme2 framework,

covering both first-order (RW1) and second-order (RW2) specifications,

along with their cyclic variants and different constraint

approaches.

Model Specification

Random Walk Process Definition

Random walk models belong to the class of intrinsic Gaussian

Markov random fields (GMRFs), defined by

finite-difference operators rather than explicit

covariance functions. The unified framework in ngme2

represents all latent models as:

where is the operator matrix that defines the model structure, is the latent process vector, and represents the innovation terms.

First-Order Random Walk (RW1)

The first-order random walk models the increments between consecutive observations as independent innovations. For a sequence of locations , the RW1 process is defined as:

where are independent innovations with variance , and represents the mesh weights (spacing between consecutive locations).

Key characteristics:

- Moderate smoothness: Provides piecewise-linear behavior

- Mesh weight scaling: Innovation variance adapts to local spacing

- Irregular grid support: Handles both regular and irregular spatial or temporal grids

Second-Order Random Walk (RW2)

The second-order random walk models the second-order differences (curvature) as independent innovations. Assuming a regular grid, we have the following dynamics:

where are independent innovations with variance , where is the (constant) distance between consecutive locations.

Key characteristics:

- Enhanced smoothness: Provides smoother trajectories than RW1, ideal for curve fitting

- Curvature control: Models second-order differences for controlled smoothness

- Minimum requirement: Needs at least 3 locations due to second-order structure

Properties

Intrinsic Nature: Random walk models are intrinsic processes defined by their difference structure rather than explicit covariance functions. This leads to:

- Rank-deficient precision matrices for non-cyclic models

- Invariance under polynomial trends (constants for RW1, linear trends for RW2)

- Need for constraints to achieve proper identification

Smoothness and Dependencies:

- RW1: Moderate smoothness with local linear behavior

- RW2: High smoothness with controlled curvature

- Markov property: Local dependence leads to sparse precision matrices

- Boundary conditions: Open (free endpoints) or cyclic (periodic)

Noise Distributions: Innovation terms can follow:

- Gaussian: Traditional symmetric, light-tailed errors

- Normal Inverse Gaussian (NIG): Flexible distribution with skewness and heavy tails

- Generalized Asymmetric Laplace (GAL): Accommodates peakedness and asymmetry

Mesh Weights and Irregular Grids

The mesh weight system

enables ngme2 to handle both regular and irregular grids

for the RW1 model:

For regular grids (equally spaced): (constant), giving standard random walk behavior.

For irregular grids (varying spacing): reflects local spacing, with innovation variance adapting to local density.

Mathematical consequences for RW1:

- Scale invariance: Proper scaling across different sampling densities

- Local adaptation: Model responds to irregular sampling patterns

- Computational stability: Preserves numerical properties across grid types

Note: The RW2 model in this vignette is demonstrated with regular grids only.

Matrix Representation

The random walk process can be expressed in matrix form as .

Precision Matrix

For random walk processes with operator matrix and mesh weights , the precision matrix is:

where contains the scaled mesh weights.

For equally spaced locations (), this simplifies to: .

Important properties:

- RW1: Tri-diagonal precision matrix (sparse structure)

- RW2: Penta-diagonal precision matrix (sparse structure)

- Rank deficiency: Non-cyclic models have singular precision matrices

- Mesh adaptation: Automatic adjustment to irregular grids (for RW1)

Matrix Relationships Summary

- Operator matrix : Maps correlated random walk process to independent innovations

-

Precision matrix:

for unconstrained models. For constrained models,

is derived from the augmented matrix

that includes constraint rows

- Sparsity: Tri-diagonal (RW1) or penta-diagonal (RW2) structure enables efficient computation

- Mesh adaptation: Automatic handling of irregular grids through matrix (for RW1)

This matrix formulation provides computational advantages through

sparse operations while maintaining flexibility for irregular sampling

patterns in RW1 models and integrates seamlessly with other

ngme2 components.

Implementation in ngme2

Basic Syntax

To specify a random walk model in ngme2, use the

f() function with the model="rw1" or

model="rw2" argument within your model formula. When not

specifying the noise argument in f(), the

process defaults to Gaussian noise. For simulation purposes, it is

important to define the sigma parameter in the

noise specification, as this controls the variance of the

innovations. For estimation, however, specifying sigma is

optional since the model will automatically estimate this parameter from

the observed data.

Basic Usage Example

The ngme2 package provides flexible random walk

implementations that accommodate both regular and irregular observation

grids for RW1 models. This flexibility is essential for real-world

applications where data may have missing observations, irregular

sampling intervals, or complex temporal patterns. RW2 models in this

vignette are demonstrated with regular grids.

Setting Up Random Walk Models

Let’s begin by exploring how to specify different types of random walk models. We’ll work with both small examples for clarity and larger examples to demonstrate computational properties:

library(ngme2)

library(Matrix)

set.seed(16)

# Define different grid configurations

regular_points <- 1:5 # Simple regular grid

irregular_points <- c(1, 3, 7, 10, 15) # Grid with gaps

larger_grid <- 1:15 # Larger grid for matrix demonstrationsNotice that the irregular grid has gaps at positions 2, 4, 5, 6, 8,

9, 11, 12, 13, and 14. The ngme2 package handles these gaps

seamlessly by constructing the appropriate precision matrix structure

internally.

Model Specification with Different Constraints

Random walk models require constraints to handle their intrinsic

nature (rank-deficient precision matrices). Let’s explore the three main

approaches available in ngme2:

# Constrained approach (default): uses sum-to-zero constraint

rw1_constrained <- f(regular_points,

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 1.5)

)

# Unconstrained approach: fixes first element as reference point

rw1_unconstrained <- f(regular_points,

model = rw1(constr = FALSE),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 1.5)

)

# Cyclic approach: treats boundaries as connected (periodic)

rw1_cyclic <- f(regular_points,

model = rw1(cyclic = TRUE),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 1.5)

)

# Second-order random walk for comparison

rw2_model <- f(regular_points,

model = rw2(),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 0.8)

)Understanding the Operator Matrix Structure

The different constraint approaches result in different operator matrix structures. Let’s examine how these translate into the mathematical formulation:

# Compare operator matrix dimensions

cat("RW1 constrained K matrix:", dim(rw1_constrained$operator$K), "\n")

#> RW1 constrained K matrix: 5 5

cat("RW1 unconstrained K matrix:", dim(rw1_unconstrained$operator$K), "\n")

#> RW1 unconstrained K matrix: 5 5

cat("RW1 cyclic K matrix:", dim(rw1_cyclic$operator$K), "\n")

#> RW1 cyclic K matrix: 6 6

cat("RW2 constrained K matrix:", dim(rw2_model$operator$K), "\n")

#> RW2 constrained K matrix: 5 5

# Examine the K matrix patterns

print("RW1 Constrained - K matrix structure:")

#> [1] "RW1 Constrained - K matrix structure:"

print(as.matrix(rw1_constrained$operator$K))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

#> [1,] 0.5 1 1 1 0.5

#> [2,] -1.0 1 0 0 0.0

#> [3,] 0.0 -1 1 0 0.0

#> [4,] 0.0 0 -1 1 0.0

#> [5,] 0.0 0 0 -1 1.0

print("RW1 Unconstrained - K matrix structure:")

#> [1] "RW1 Unconstrained - K matrix structure:"

print(as.matrix(rw1_unconstrained$operator$K))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

#> [1,] 1 0 0 0 0

#> [2,] -1 1 0 0 0

#> [3,] 0 -1 1 0 0

#> [4,] 0 0 -1 1 0

#> [5,] 0 0 0 -1 1

print("RW1 Cyclic - K matrix structure:")

#> [1] "RW1 Cyclic - K matrix structure:"

print(as.matrix(rw1_cyclic$operator$K))

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

#> [1,] 0 0.5 1 1 1 0.5

#> [2,] 1 1.0 -1 0 0 0.0

#> [3,] 1 0.0 1 -1 0 0.0

#> [4,] 1 0.0 0 1 -1 0.0

#> [5,] 1 0.0 0 0 1 -1.0

#> [6,] 1 -1.0 0 0 0 1.0Each constraint type creates a distinct pattern:

- Constrained: First row contains sum-to-zero constraint weights, subsequent rows are difference operators

-

Unconstrained: First row fixes the reference point

(W₁ = 0), subsequent rows are standard differences

- Cyclic: Constraint row spans all locations, differences connect endpoints to create periodic structure

Handling Irregular Grids

One of ngme2’s strengths is seamless handling of

irregular observation patterns through internal mapping:

# Create model on irregular grid

rw1_irregular <- f(irregular_points,

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 1.0)

)

# Examine the mapping between observed and internal grid

print("User-specified locations:")

#> [1] "User-specified locations:"

print(irregular_points)

#> [1] 1 3 7 10 15

print("Internal mesh locations:")

#> [1] "Internal mesh locations:"

print(rw1_irregular$operator$mesh$loc)

#> [1] 1 3 7 10 15

print("Mapping matrix dimensions:")

#> [1] "Mapping matrix dimensions:"

print(dim(rw1_irregular$A))

#> [1] 5 5The mapping matrix A bridges the gap between the irregular observations and the complete internal grid structure required for the random walk formulation.

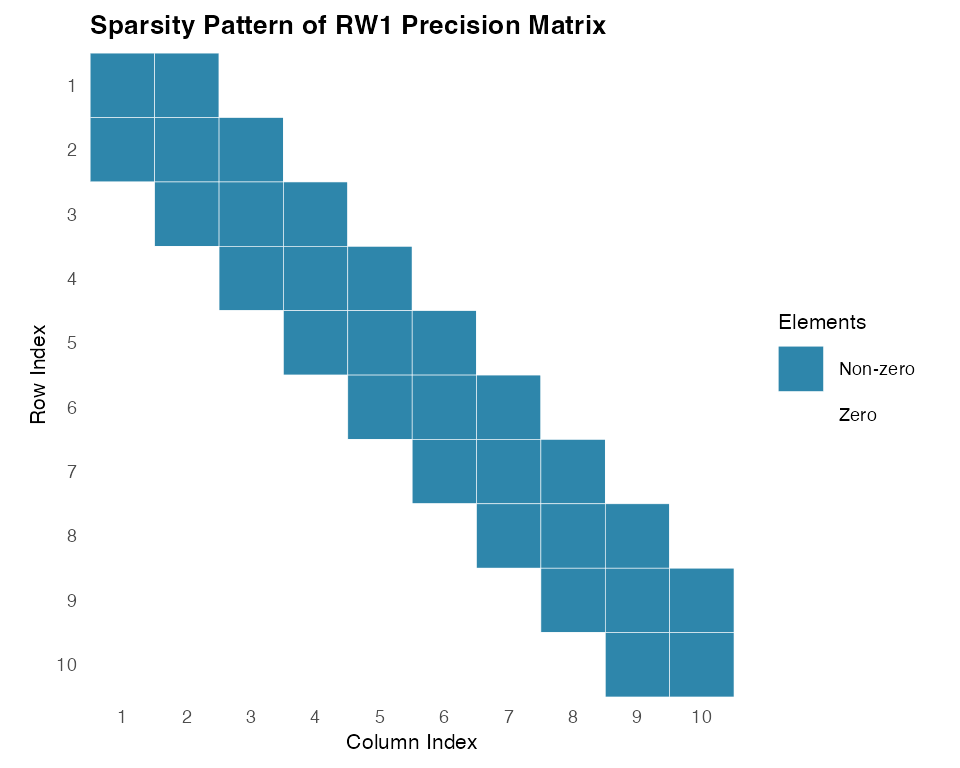

Matrix Structure and Computational Efficiency

This matrix formulation provides several computational benefits, particularly in terms of memory efficiency and processing speed. To better demonstrate the sparsity characteristics of random walk models, let’s examine the unconstrained approach which shows the classic tridiagonal structure:

# Load Matrix package for sparse matrix operations

library(Matrix)

# Create unconstrained model to show classic sparse structure

rw1_sparse <- f(1:10, # Use 10 points for clear demonstration

model = rw1(constr = FALSE), # Unconstrained for classic tridiagonal sparsity

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 1.0)

)

# The precision matrix is computed as Q = (K^T K) / sigma^2

sigma2 <- 1.0

Q_matrix <- (t(rw1_sparse$operator$K) %*% rw1_sparse$operator$K) / sigma2

print("RW1 Unconstrained Precision Matrix:")

#> [1] "RW1 Unconstrained Precision Matrix:"

print(Q_matrix)

#> 10 x 10 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

#>

#> [1,] 2 -1 . . . . . . . .

#> [2,] -1 2 -1 . . . . . . .

#> [3,] . -1 2 -1 . . . . . .

#> [4,] . . -1 2 -1 . . . . .

#> [5,] . . . -1 2 -1 . . . .

#> [6,] . . . . -1 2 -1 . . .

#> [7,] . . . . . -1 2 -1 . .

#> [8,] . . . . . . -1 2 -1 .

#> [9,] . . . . . . . -1 2 -1

#> [10,] . . . . . . . . -1 1Now let us examine the sparsity pattern of the precision matrix, which is crucial for computational efficiency:

Now let us examine the sparsity pattern of the precision matrix, which is crucial for computational efficiency:

# Check sparsity (important for computational efficiency)

Q_dense <- as.matrix(Q_matrix)

total_elements <- nrow(Q_matrix) * ncol(Q_matrix)

zero_elements <- sum(abs(Q_dense) < 1e-10)

sparsity <- zero_elements / total_elements

print(paste("Sparsity of precision matrix:", round(sparsity * 100, 1), "%"))

#> [1] "Sparsity of precision matrix: 72 %"The unconstrained RW1 model shows clear tridiagonal sparsity structure, with most elements being zero. This sparsity becomes even more pronounced for longer series, making random walk models computationally efficient for large-scale applications.

Finally, let us demonstrate how different error variances affect the precision matrix:

# Demonstrate how different error variances affect the precision matrix

sigma2_values <- c(0.5, 2.0, 4.0)

for (sigma2_test in sigma2_values) {

Q_scaled <- (t(rw1_sparse$operator$K) %*% rw1_sparse$operator$K) / sigma2_test

print(paste(

"With sigma^2 =", sigma2_test,

", Q[1,1] =", round(Q_scaled[1, 1], 3),

"(scaled by factor 1/", sigma2_test, ")"

))

}

#> [1] "With sigma^2 = 0.5 , Q[1,1] = 4 (scaled by factor 1/ 0.5 )"

#> [1] "With sigma^2 = 2 , Q[1,1] = 1 (scaled by factor 1/ 2 )"

#> [1] "With sigma^2 = 4 , Q[1,1] = 0.5 (scaled by factor 1/ 4 )"Key Takeaways:

- Unconstrained models exhibit classic tridiagonal sparse structure ideal for computational efficiency

- Constrained models sacrifice some sparsity for theoretical identifiability properties

- Sparsity increases with series length, making random walk models scalable to large datasets

- The

ngme2package automatically handles sparse matrix operations for all constraint types

The resulting precision matrix

exhibits clear tridiagonal sparsity structure characteristic of

unconstrained random walk models. This sparsity reflects the local

dependency structure inherent in random walk processes and enables

efficient computation and storage, making ngme2 practical

for large-scale spatial and temporal modeling.

Simulation

Understanding random walk model behavior through simulation helps

build intuition about smoothness properties and the impact of different

noise distributions. The ngme2 package provides

straightforward simulation capabilities that allow us to explore these

characteristics systematically.

Setting Up the Simulation Environment

First, let us prepare our environment and define the basic parameters for our simulations:

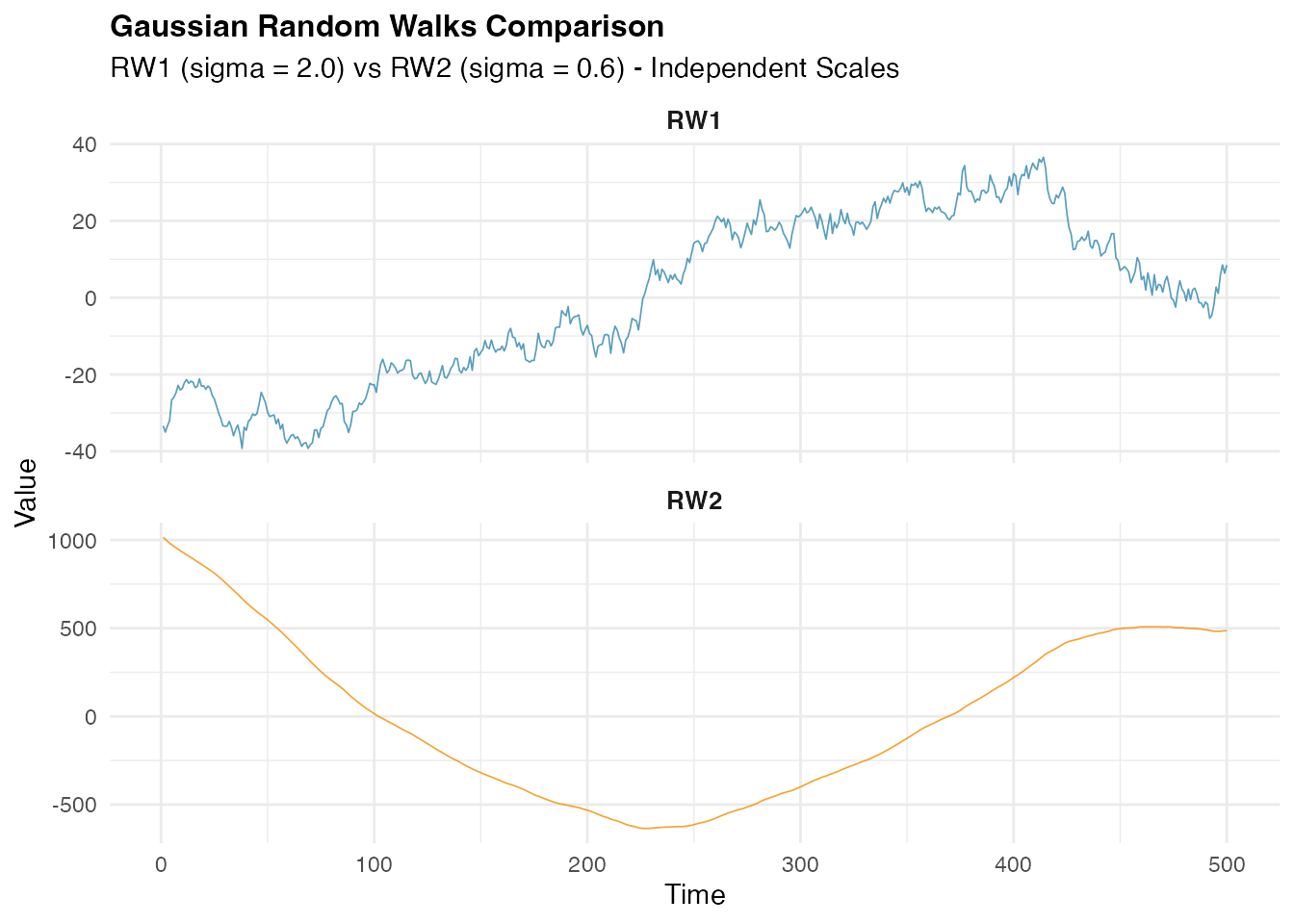

Gaussian Random Walk Simulation

We begin with the traditional Gaussian random walk model, which

assumes normally distributed innovations. This serves as our baseline

for comparison. First, we create the random walk model objects using the

f() function, which specifies the model structure,

parameters, and noise distribution. The f() function

returns a model object that contains all the necessary information for

simulation and estimation, including the spatial dependence structure

and the Gaussian noise specification.

# Define RW1 model with Gaussian noise

rw1_gaussian <- f(time_index,

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 2.0)

)

# Define RW2 model with Gaussian noise (smaller sigma for comparison)

rw2_gaussian <- f(time_index,

model = rw2(),

noise = noise_normal(sigma = 0.6)

)In the second step, we obtain sample realizations from these models

using the simulate() method, which generates random samples

according to the specified random walk process. The

simulate() method takes the model object as input along

with optional arguments such as the random seed

(seed = 456) for reproducibility and the number of

simulations (nsim = 1). This two-step approach separates

model specification from sample generation, providing flexibility for

multiple simulations or parameter exploration.

# Generate realizations from the random walk models

W1_gaussian <- simulate(rw1_gaussian, seed = 456, nsim = 1)[[1]]

W2_gaussian <- simulate(rw2_gaussian, seed = 456, nsim = 1)[[1]]Let us visualize the simulated Gaussian random walk processes and examine their characteristics:

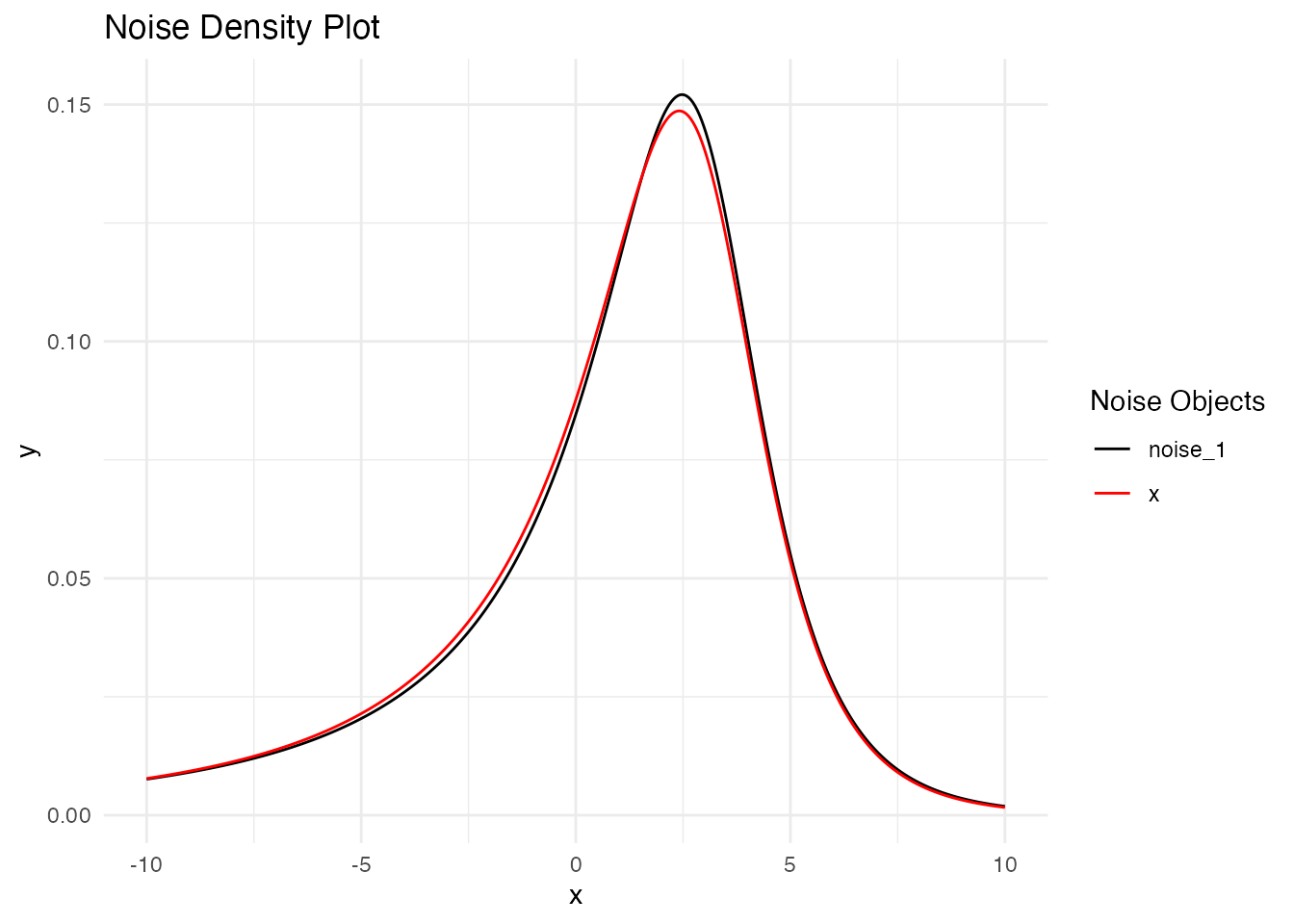

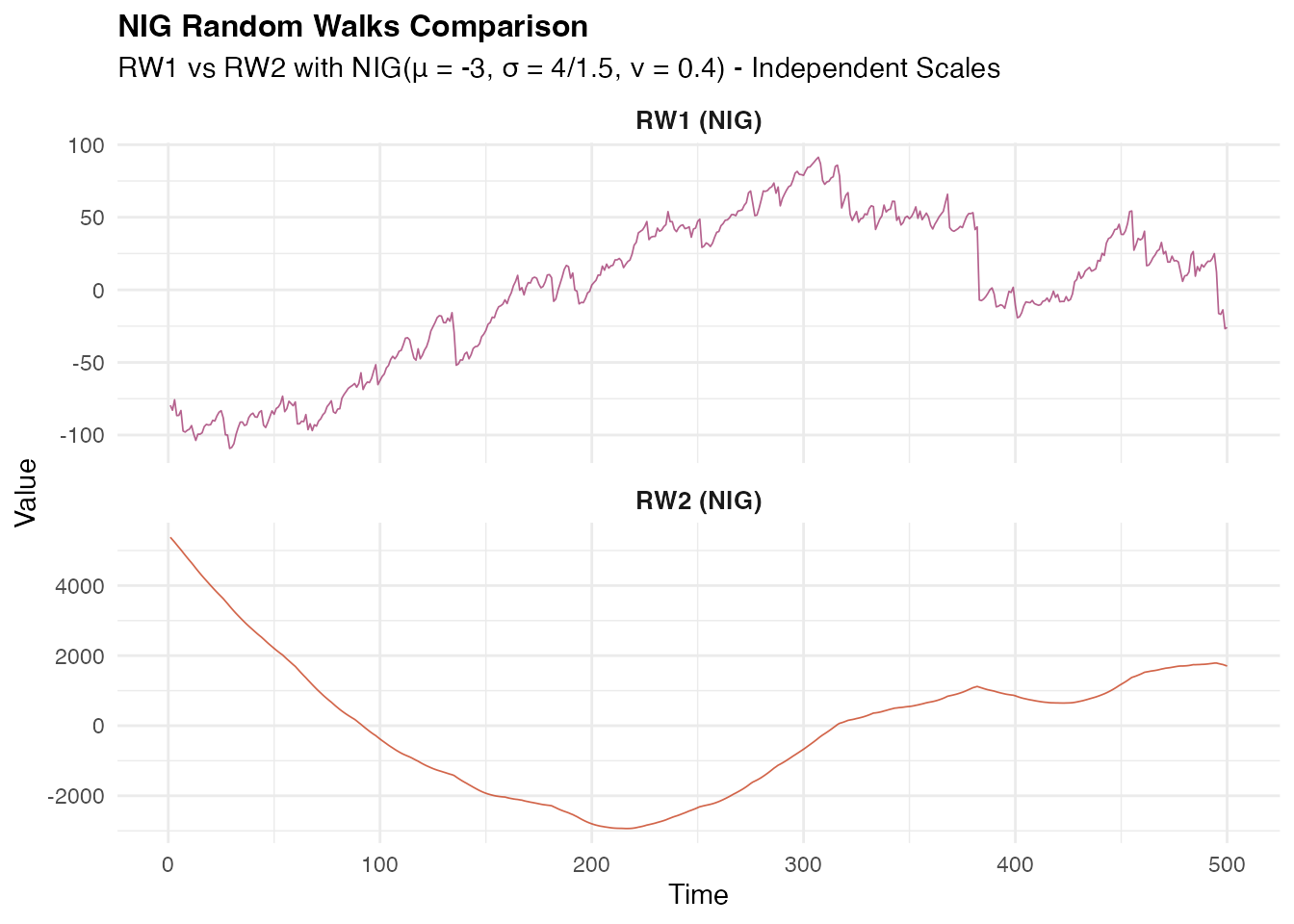

NIG Random Walk Simulation

Now let us explore the flexibility of non-Gaussian innovations using

the Normal Inverse Gaussian (NIG) distribution, which can capture

asymmetry and heavy tails. Here we create random walk model objects with

NIG innovations using the f() function. The NIG

distribution is specified through noise_nig() with three

parameters: mu = -3 (location parameter introducing

asymmetry), sigma = 4 (scale parameter controlling spread),

and nu = 0.4 (shape parameter governing tail

heaviness).

# Define RW1 model with NIG noise

rw1_nig <- f(time_index,

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_nig(mu = -3, sigma = 4, nu = 0.4)

)

# Define RW2 model with NIG noise

rw2_nig <- f(time_index,

model = rw2(),

noise = noise_nig(mu = -3, sigma = 1.5, nu = 0.4)

)We then generate sample realizations using the

simulate() method with a different random seed

(seed = 16) to ensure independent samples from our Gaussian

example. The resulting series will exhibit the characteristic features

of NIG innovations while maintaining the random walk spatial correlation

structure.

# Generate realizations from the NIG random walk models

W1_nig <- simulate(rw1_nig, seed = 16, nsim = 1)[[1]]

W2_nig <- simulate(rw2_nig, seed = 16, nsim = 1)[[1]]Next, we visualize the NIG random walk processes and their characteristics:

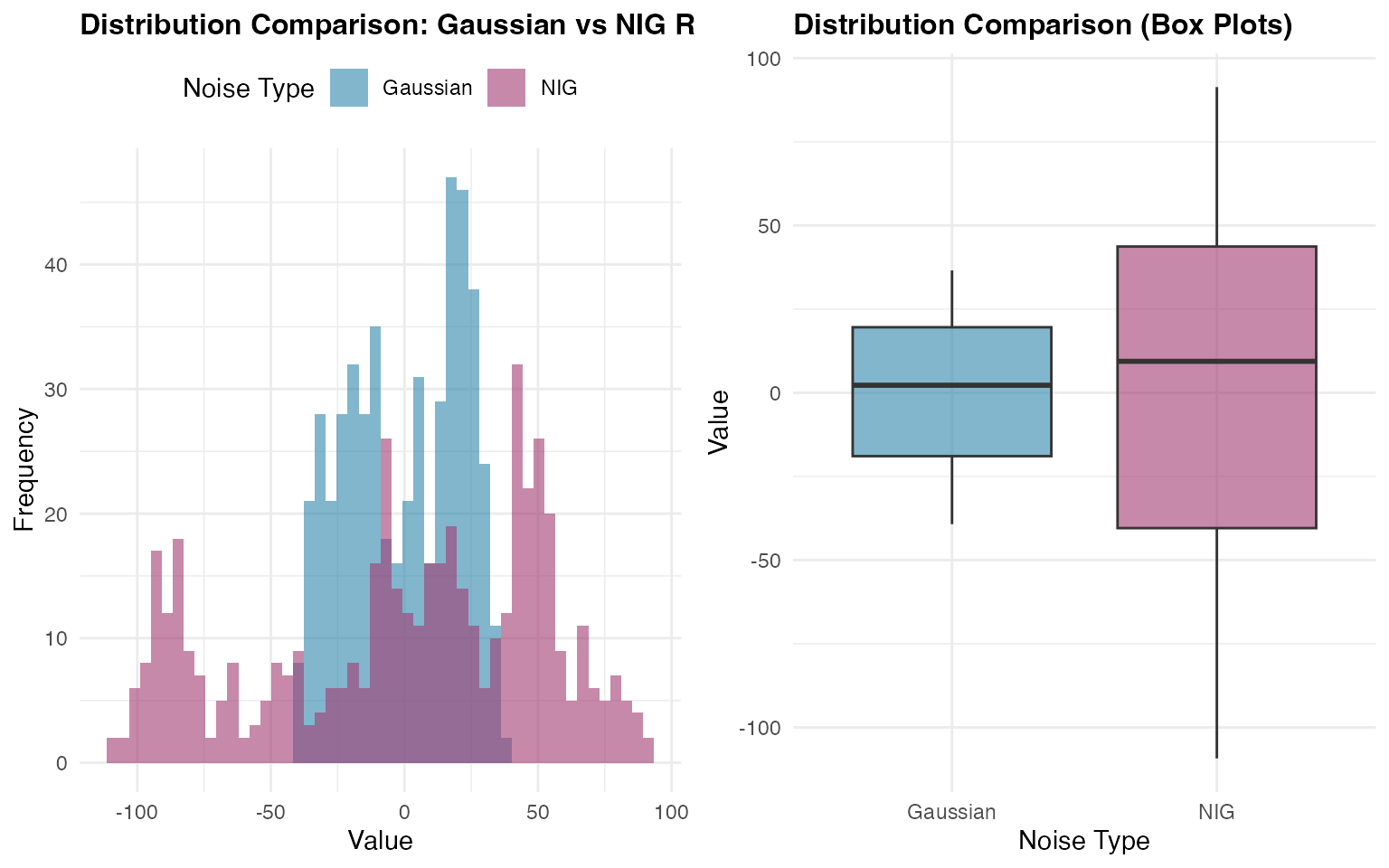

Comparing Distributions

A key advantage of the NIG distribution is its ability to model asymmetric and heavy-tailed behavior. To better understand the differences between Gaussian and NIG innovations, we will prepare the data for a direct comparison of the marginal distributions. This analysis will highlight how the choice of noise distribution affects the overall behavior of the random walk process:

# Combine data for comparison

comparison_data <- data.frame(

value = c(W1_gaussian, W1_nig),

type = rep(c("Gaussian", "NIG"), each = n_obs)

)Now we create comparative visualizations to examine the distributional differences between the two random walk processes:

The comparison reveals how the NIG distribution captures different tail behavior and potential asymmetry compared to the Gaussian case, while maintaining the overall random walk structure.

Estimation

Model estimation in ngme2 involves fitting random walk

models to observed data using advanced optimization techniques. We’ll

demonstrate this process using our simulated NIG data combined with

fixed effects and measurement noise.

Preparing the Data

Let us create a realistic dataset with fixed effects, latent RW2 structure, and measurement noise:

# Define fixed effects and covariates

feff <- c(-1, 2, 0.5)

x1 <- runif(n_obs, 0, 10)

x2 <- rexp(n_obs, 1 / 10)

x3 <- rnorm(n_obs, mean = 10, sd = 0.5)

X <- model.matrix(~ 0 + x1 + x2 + x3)

# Create response variable with fixed effects, latent process, and measurement noise

Y <- as.numeric(X %*% feff) + W1_nig + rnorm(n_obs, sd = 2)

# Prepare data frame

model_data <- data.frame(x1 = x1, x2 = x2, x3 = x3, Y = Y)Model Specification and Fitting

We specify our model using the ngme function,

incorporating both fixed effects and the latent random walk process. The

ngme() function follows R’s standard modeling approach by

accepting a formula object that defines the relationship between the

response variable and both fixed and latent effects:

# Fit the model

ngme_out <- ngme(

Y ~ 0 + x1 + x2 + x3 + f(

1:n_obs,

name = "my_rw",

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_nig()

),

data = model_data,

control_opt = control_opt(

optimizer = adam(),

burnin = 100,

iterations = 2000,

std_lim = 0.02,

n_parallel_chain = 4,

n_batch = 5,

verbose = FALSE,

print_check_info = FALSE,

seed = 3

)

)The formula Y ~ 0 + x1 + x2 + x3 + f(...) specifies that

the response variable Y depends on three fixed effects

(x1, x2, x3) with no intercept

(the 0 term), plus a latent RW1 process defined through the

f() function. The latent model is specified with

f(1:n_obs, name = "my_rw", model = "rw1", noise = noise_nig()),

where we assign a name to the process for later reference and specify

NIG innovations without fixing the parameters (allowing them to be

estimated).

The control_opt() function manages the optimization

process through several key parameters:

-

optimizer = adam(): Uses the Adam optimizer, an adaptive gradient-based algorithm well-suited for complex likelihood surfaces -

iterations = 1000: Sets the maximum number of optimization iterations -

burnin = 100: Specifies initial iterations for algorithm stabilization before convergence assessment -

n_parallel_chain = 4: Runs 4 parallel optimization chains to improve convergence reliability and parameter estimation robustness -

std_lim = 0.01: Sets the convergence criterion based on parameter standard deviation across chains -

n_batch = 10: Number of intermediate convergence checks during optimization -

seed = 3: Ensures reproducible results across runs

This optimization setup balances computational efficiency with estimation reliability, particularly important for complex models with non-Gaussian latent processes. Let us examine the fitted model results:

# Display model summary

ngme_out

#> *** Ngme object ***

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> x1 x2 x3

#> -0.725 1.680 0.479

#>

#> Models:

#> $my_rw

#> Model type: Random walk (order 1)

#> No parameter.

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = -3.37

#> sigma = 2.03

#> nu = 0.426

#>

#> Measurement noise:

#> Noise type: NORMAL

#> Noise parameters:

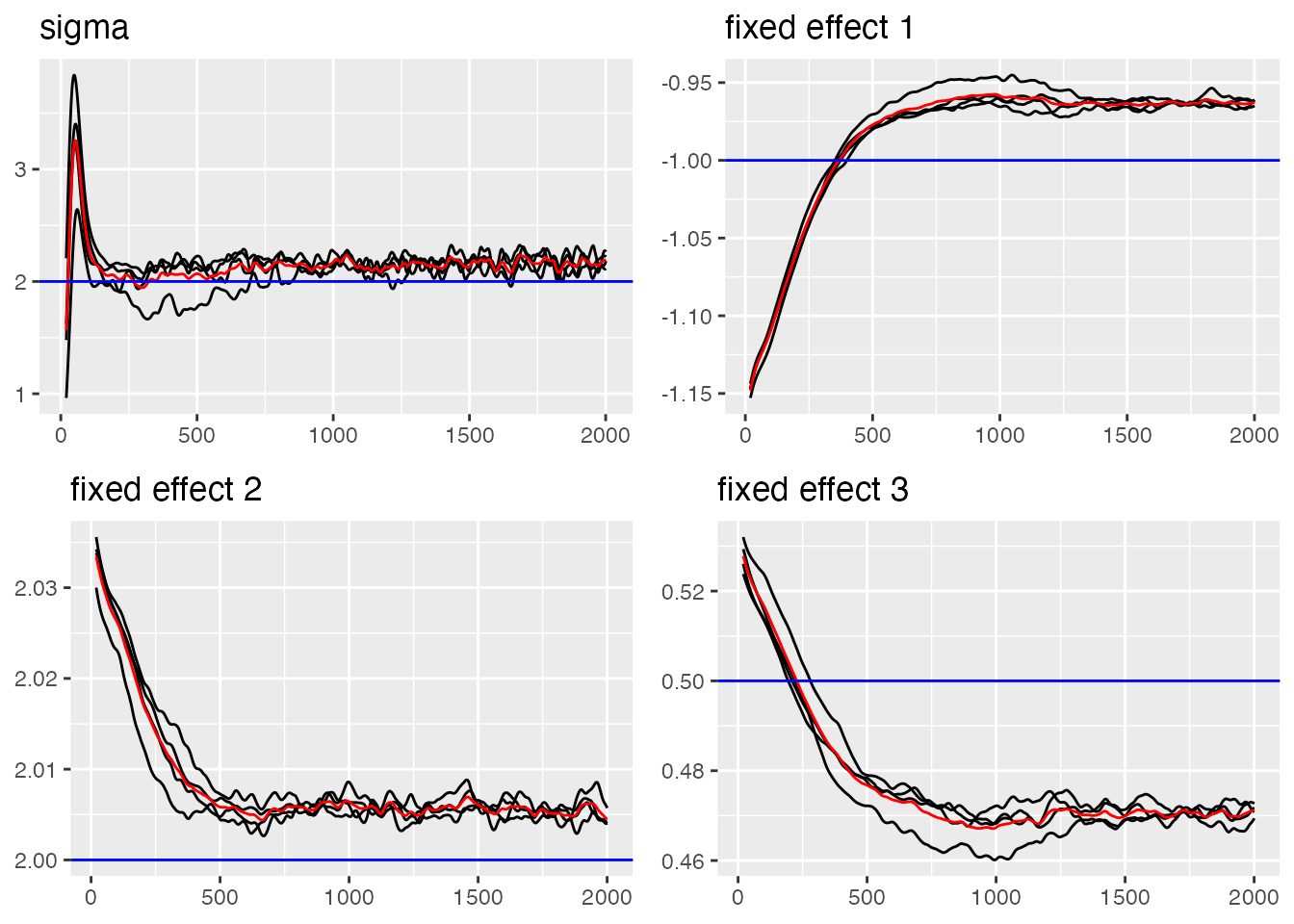

#> sigma = 5.21Convergence Diagnostics

Assessing convergence is crucial for reliable parameter estimates. We

will use the built-in traceplot function from

ngme2 to examine the convergence of our parameters:

# Trace plot for sigma and fixed effects (blue lines indicate true value)

traceplot(ngme_out, "data", hline = c(2, -1, 2, 0.5), moving_window = 20)

#> Last estimates:

#> $sigma

#> [1] 5.643671

#>

#> $`fixed effect 1`

#> [1] -0.6948023

#>

#> $`fixed effect 2`

#> [1] 1.645725

#>

#> $`fixed effect 3`

#> [1] 0.4749191Now let us examine the convergence of the RW1 process parameters:

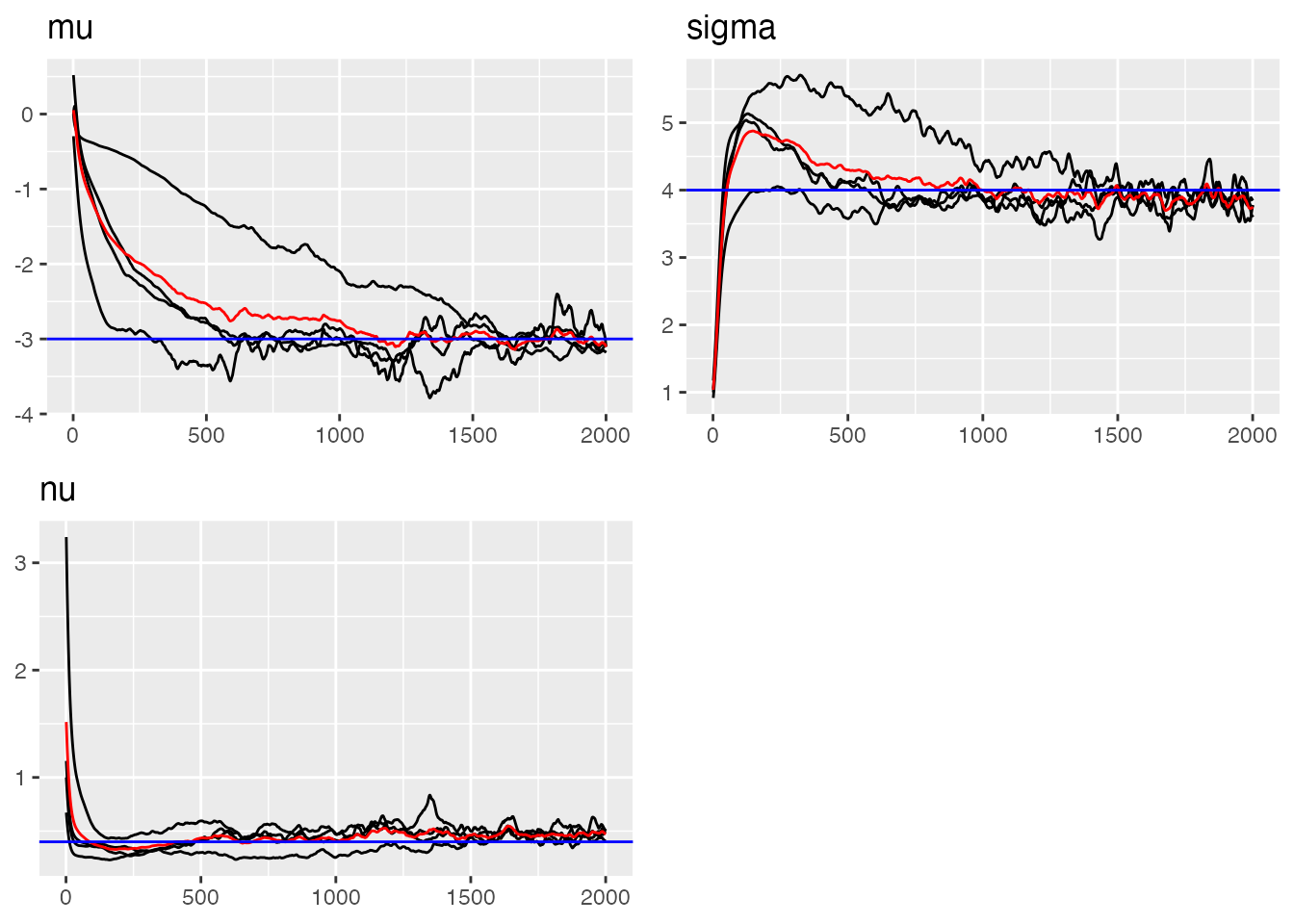

# Trace plots for RW1 parameters (blue lines indicate true value)

traceplot(ngme_out, "my_rw", hline = c(-3, 4, 0.4))

#> Last estimates:

#> $mu

#> [1] -3.500722

#>

#> $sigma

#> [1] 1.800996

#>

#> $nu

#> [1] 0.4663539Parameter Estimates Summary

Let us examine the final parameter estimates and compare them with

the true values using the ngme_result() function:

# Parameter Estimates for Fixed Effects and Measurement Noise

params_data <- ngme_result(ngme_out, "data")

# Fixed Effects

print(data.frame(

Truth = c(-1, 2, 0.5),

Estimates = as.numeric(params_data$beta),

row.names = names(params_data$beta)

))

#> Truth Estimates

#> x1 -1.0 -0.7249672

#> x2 2.0 1.6804133

#> x3 0.5 0.4793452

# Measurement Noise

print(data.frame(Truth = 2.0, Estimate = params_data$sigma, row.names = "sigma"))

#> Truth Estimate

#> sigma 2 5.208464

cat("\n")

# RW1 Process Parameters

params_rw1 <- ngme_result(ngme_out, "my_rw")

print(data.frame(

Truth = c(mu = -3.0, sigma = 4.0, nu = 0.4),

Estimates = unlist(params_rw1)

))

#> Truth Estimates

#> mu -3.0 -3.3747806

#> sigma 4.0 2.0325484

#> nu 0.4 0.4264659Interpolation

Once we have fitted a random walk model using ngme2, we

can use it for interpolating missing observations. Random walk models

are particularly well-suited for interpolation tasks because they

exploit the spatial/temporal smoothness of the underlying process,

making them effective when dealing with irregular sampling or gaps in

the observation grid.

Interpolation for Missing Values

Random walk models are well suited for interpolating missing values because they exploit the spatial dependence between neighboring observations. This makes them especially useful when dealing with irregular sampling or short gaps in spatial or temporal data.

To illustrate this, we introduce artificial gaps at different points in the series and use the RW1 model to reconstruct the missing values:

gap1_indices <- 151:155 # Early gap (around 30% of series)

gap2_indices <- 250:254 # Middle gap (around 50% of series)

gap3_indices <- 420:424 # Late gap (around 85% of series)

all_gap_indices <- c(gap1_indices, gap2_indices, gap3_indices)

Y_true_gaps <- Y[all_gap_indices]

train_indices_interp <- setdiff(1:n_obs, all_gap_indices)

model_data_train_interp <- model_data[train_indices_interp, ]

Y_train_vector <- Y[train_indices_interp]

cat("Total gaps to interpolate:", length(all_gap_indices), "\n")

#> Total gaps to interpolate: 15

cat("Training observations:", length(train_indices_interp), "\n")

#> Training observations: 485Fitting Model for Interpolation

The interpolation model is fitted using only the non-gap

observations. The indices in the f() function correspond to

the actual observation locations, allowing the model to handle irregular

grids naturally:

ngme_out_interp <- ngme(

Y_train_vector ~ 0 + x1 + x2 + x3 + f(

train_indices_interp,

name = "my_rw_interp",

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_nig()

),

data = model_data_train_interp,

control_opt = control_opt(

optimizer = adam(),

burnin = 100,

iterations = 1000,

std_lim = 0.01,

n_parallel_chain = 4,

n_batch = 10,

verbose = FALSE,

print_check_info = FALSE,

seed = 42

)

)Making Interpolation Predictions

The interpolation predictions are generated for the gap locations using the corresponding covariate values. The model leverages spatial correlation from neighboring observed points to estimate the missing values:

gap_covariates <- data.frame(

x1 = x1[all_gap_indices],

x2 = x2[all_gap_indices],

x3 = x3[all_gap_indices]

)

interpolation_pred <- predict(

ngme_out_interp,

map = list(my_rw_interp = all_gap_indices),

data = gap_covariates,

type = "lp",

estimator = c("mean", "sd", "0.5q", "0.95q"),

sampling_size = 1000,

seed = 42

)

interp_mean <- interpolation_pred$mean

interp_sd <- interpolation_pred$sd

interp_lower <- interpolation_pred[["0.5q"]]

interp_upper <- interpolation_pred[["0.95q"]]Technical Interpolation Results

The interpolation performance can be assessed by comparing predicted values with the true (known) values at gap locations. These metrics demonstrate the effectiveness of spatial correlation for missing value estimation:

interp_errors <- interp_mean - Y_true_gaps

rmse_interp <- sqrt(mean(interp_errors^2))

mae_interp <- mean(abs(interp_errors))

correlation_interp <- cor(interp_mean, Y_true_gaps)

in_interval_90_interp <- (Y_true_gaps >= interp_lower) & (Y_true_gaps <= interp_upper)

coverage_90_interp <- mean(in_interval_90_interp)

cat("RMSE:", round(rmse_interp, 3), "\n")

#> RMSE: 4.944

cat("MAE:", round(mae_interp, 3), "\n")

#> MAE: 4.092

cat("Correlation:", round(correlation_interp, 3), "\n")

#> Correlation: 0.992

cat("90% Interval Coverage:", round(coverage_90_interp * 100, 1), "%\n")

#> 90% Interval Coverage: 26.7 %

print(data.frame(

Time = all_gap_indices[1:10],

Observed = round(Y_true_gaps[1:10], 2),

Interpolated = round(interp_mean[1:10], 2),

Lower_90 = round(interp_lower[1:10], 2),

Upper_90 = round(interp_upper[1:10], 2)

))

#> Time Observed Interpolated Lower_90 Upper_90

#> 1 151 -14.39 -17.17 -17.21 -12.88

#> 2 152 -16.94 -15.41 -15.46 -11.24

#> 3 153 -16.52 -15.10 -15.16 -11.05

#> 4 154 -17.10 -15.97 -16.03 -12.04

#> 5 155 7.52 2.55 2.48 6.36

#> 6 250 68.17 58.12 58.13 63.12

#> 7 251 43.51 35.76 35.72 40.63

#> 8 252 43.77 46.17 46.08 50.89

#> 9 253 39.76 43.82 43.69 48.40

#> 10 254 86.37 78.44 78.26 82.88Posterior Simulation

After fitting and validating our random walk model, we can generate posterior samples to quantify uncertainty in both the latent process and the response predictions. This Bayesian approach provides comprehensive uncertainty characterization beyond simple point estimates.

Generating Posterior Samples

The ngme2 package provides functionality to generate

posterior samples through the ngme_post_samples() function.

These samples represent different plausible realizations of the latent

random walk process given the observed data and estimated

parameters:

posterior_samples <- ngme_post_samples(ngme_out)

cat("Number of time points:", nrow(posterior_samples), "\n")

#> Number of time points: 500

cat("Number of posterior samples:", ncol(posterior_samples), "\n")

#> Number of posterior samples: 100

cat("Sample names:", names(posterior_samples)[1:5], "...\n")

#> Sample names: sample_1 sample_2 sample_3 sample_4 sample_5 ...Latent Process Posterior Analysis

We first analyze the posterior uncertainty in the latent random walk process (W). The posterior samples allow us to quantify how well we can recover the underlying spatial structure:

W_posterior_mean <- apply(posterior_samples, 1, mean)

W_posterior_sd <- apply(posterior_samples, 1, sd)

W_posterior_q025 <- apply(posterior_samples, 1, function(x) quantile(x, 0.025))

W_posterior_q975 <- apply(posterior_samples, 1, function(x) quantile(x, 0.975))

comparison_data <- data.frame(

time = 1:n_obs,

true_W = W1_nig,

posterior_mean = W_posterior_mean,

posterior_lower = W_posterior_q025,

posterior_upper = W_posterior_q975

)

cat(

"Mean absolute difference from true values:",

round(mean(abs(W_posterior_mean - W1_nig)), 3), "\n"

)

#> Mean absolute difference from true values: 2.232

cat(

"Average posterior standard deviation:",

round(mean(W_posterior_sd), 3), "\n"

)

#> Average posterior standard deviation: 2.827Latent Process Uncertainty Visualization

This visualization shows how well the model recovers the underlying latent random walk process by comparing the posterior estimates with the true latent values:

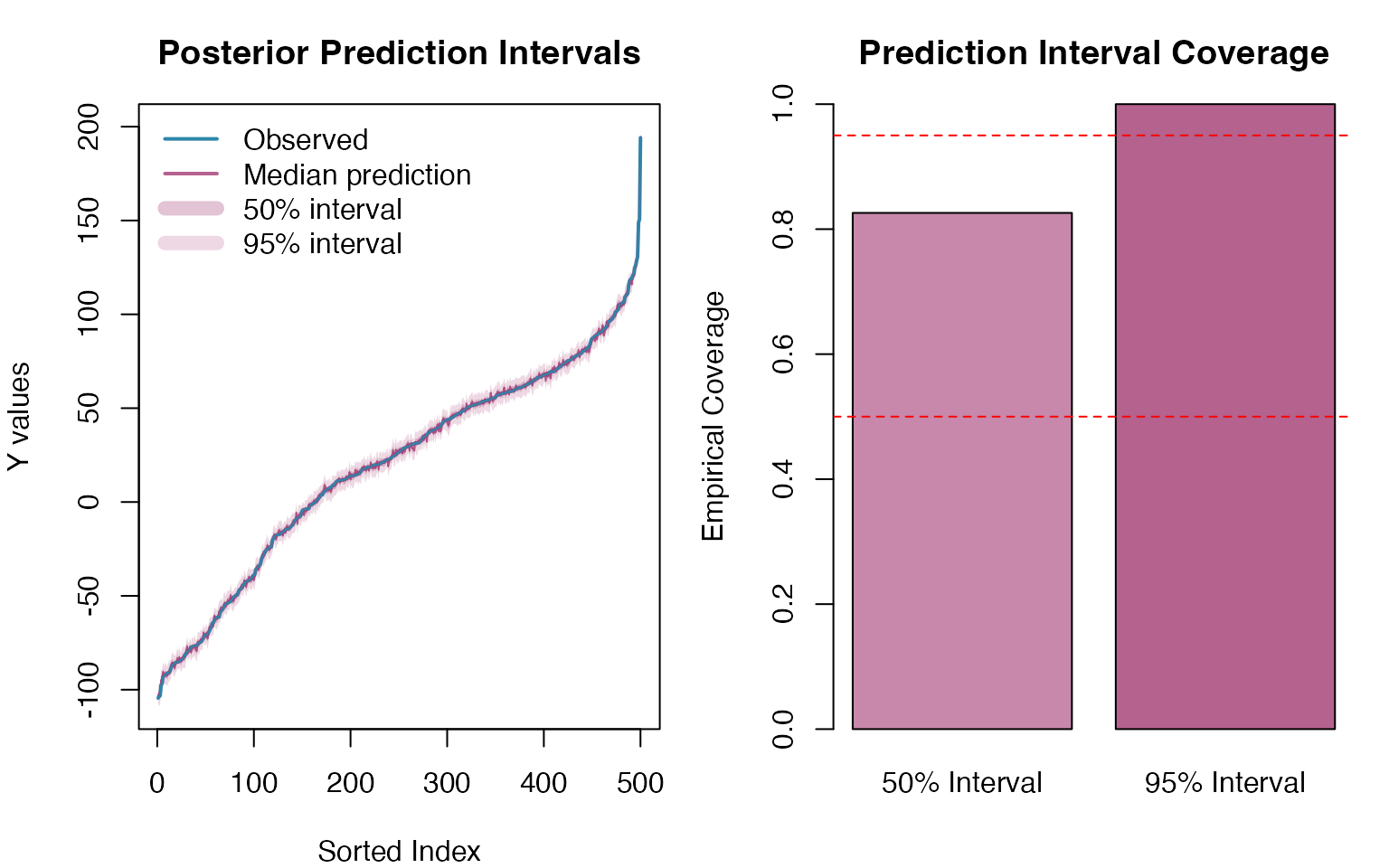

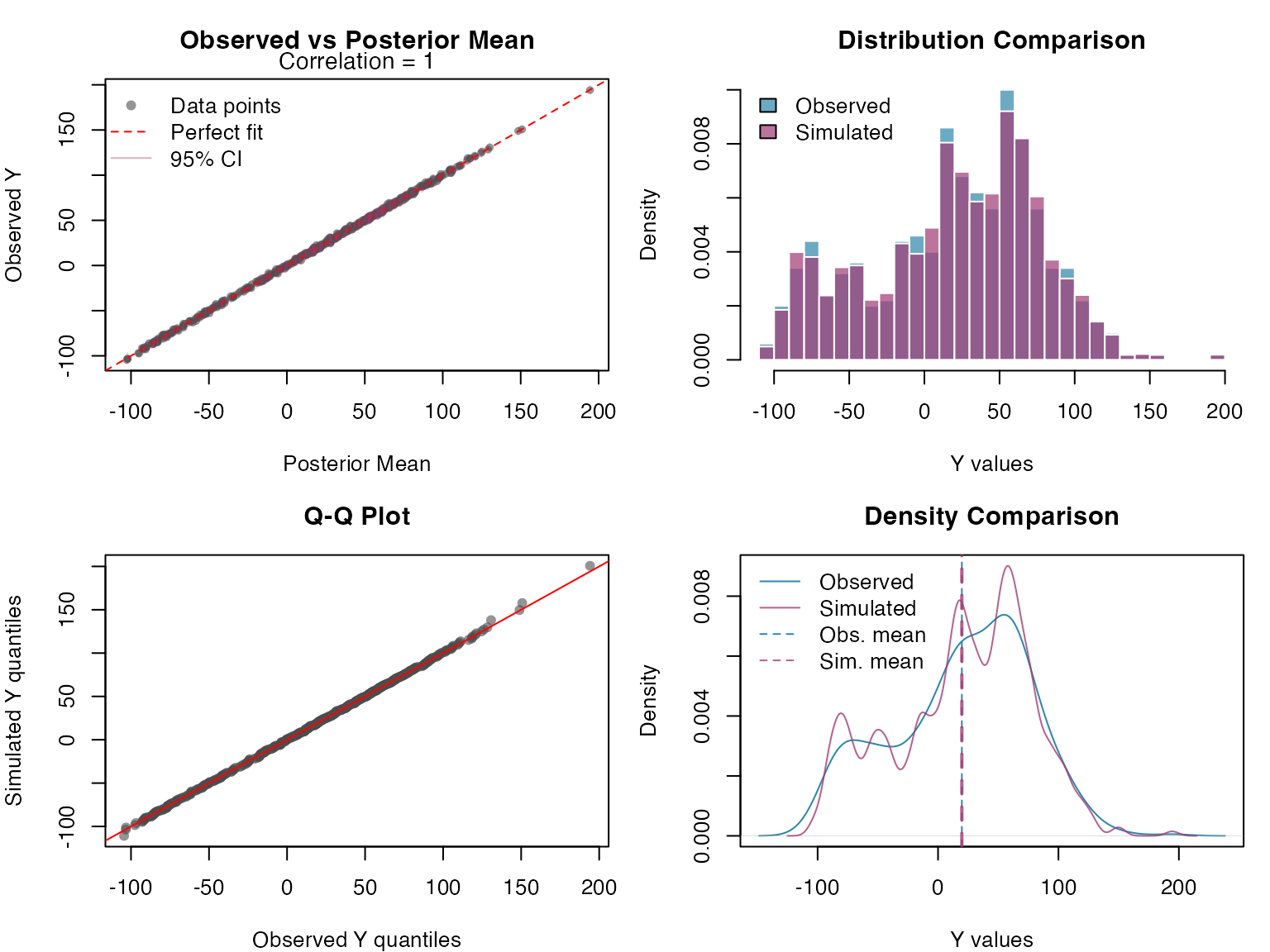

Response Variable Posterior Predictive Check

We now assess model adequacy by generating posterior predictive samples for the response variable (Y) and comparing them with the observed data:

n_sims <- 300

# Generate posterior predictive samples for Y using simulate()

Y_sim <- simulate(ngme_out, posterior = TRUE, m_noise = TRUE, nsim = n_sims)

# Convert to matrix for easier handling

Y_sim_matrix <- as.matrix(Y_sim)

Finally, we assess the calibration of our prediction intervals by examining how well the posterior predictive samples capture the observed data: