Ngme2 - A Unified, Efficient, and Flexible non-Gaussian Modeling Framework

2026-03-02

Source:vignettes/ngme2.Rmd

ngme2.RmdIntroduction

Latent Gaussian models (LGMs) have emerged as a cornerstone of modern statistical inference, providing a powerful framework for modeling hierarchical dependencies in data.

Despite their versatility, LGMs encounter fundamental limitations when applied to data exhibiting non-Gaussian characteristics. The Gaussian assumption imposes inherent constraints that may be overly restrictive for many real-world phenomena. Some common non-Gaussian features exhibited by real world data include asymmetry, heavy tails, and non-smoothness.

ngme2

R package is a unified, efficient, and flexible modeling software for

modeling non-Gaussian data. It is the updated version of ngme, which

was first introduced in (Asar et al.

2020)

Features

- Support temporal models like AR(1), Ornstein−Uhlenbeck and random walk processes, and spatial models like Matern fields.

- Support latent processes driven by non-Gaussian noises (normal inverse Gaussian(NIG), generalized asymmetric Laplace (GAL), etc).

- Support non-Gaussian, and correlated measurement noises.

- Support kriging prediction at unknown locations.

- Support latent processes and random-effects model for longitudinal data.

- Support the bivariate type-G model, which can model 2 non-Gaussian fields jointly (Bolin and Wallin 2019).

- Support the separable space-time model, and non-separable space-time model.

- Support the user-defined model via

genericandgeneric_nsfunctions. - Provide estimation diagnostics, and cross-validation for model selection.

Model Framework

The package Ngme2 implements the latent linear

non-Gaussian model (LLnGM) framework, which uses flexible operator

formulations to describe data, latent processes, and noise in a unified

way:

The data model links observations to the latent process through the observation matrix , adds fixed effects , and allows non-Gaussian measurement noise .

The process model specifies the core dependency structure of via the operator matrix , which is driven by potentially non-Gaussian noise . This operator-based formulation unifies a wide spectrum of model structures, from simple random effects to complex spatio-temporal patterns.

Here denotes element-wise multiplication. The noise model defines and through normal mean-variance mixtures conditioned on the GIG mixing vectors and . The parameter vector collects all model parameters.

Here is a simple template for using the core function

ngme to model the single response:

ngme(

formula=Y ~ x1 + x2 + f(index, model=ar1(mesh_1d), noise=noise_nig()),

data=data.frame(Y=Y, x1=x1, x2=x2, index=index),

family = "normal"

)Here, function f is for modeling the stochastic process

W with Gaussian or non-Gaussian noise, we will discuss this later.

noise stands for the measurement noise distribution. In

this case, the model will have a Gaussian likelihood.

Non-Gaussian Model

Here we assume the non-Gaussian process is a type-G Lévy process, whose increments can be represented as location-scale mixtures: where are parameters, is independent of , and is a positive infinitely divisible random variable. This results in the following form, where is the operator part:

where and can be non-stationary.

One example in ngme2 is the normal inverse Gaussian

(NIG) noise, where

follows an Inverse Gaussian distribution with parameter

(IG(,

)).

A random variable follows an inverse Gaussian distribution with parameters and , denoted by , if it has probability density function (pdf) given by We can generate samples from an inverse Gaussian distribution with parameters and by generating samples from the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution with parameters , and . The rGIG function can be used to generate samples from the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution.

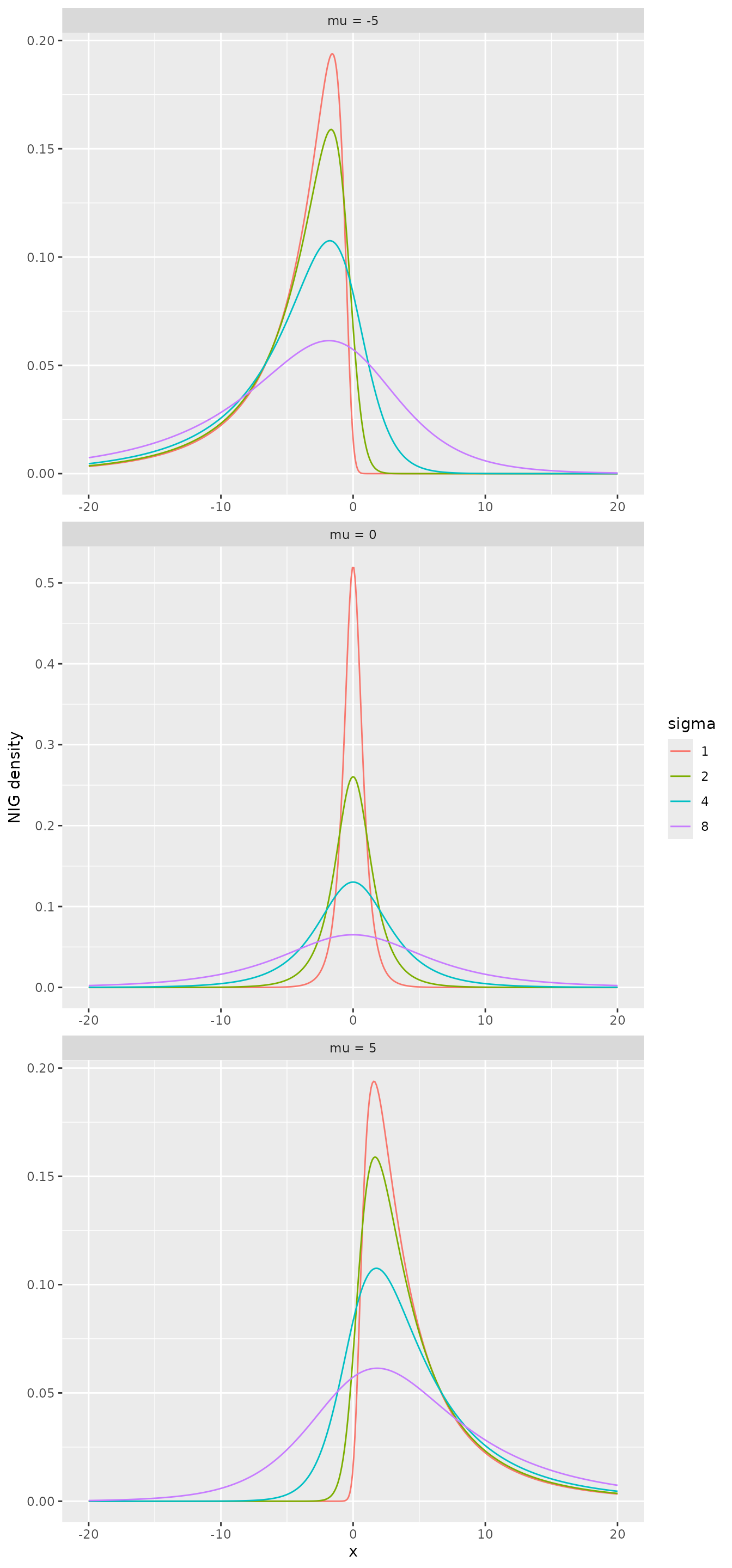

If , and , with independent of , then follows a normal inverse Gaussian (NIG) distribution with pdf where is a modified Bessel function of the third kind. In this form, the NIG density is overparameterized, so we set , which results in . Thus, we have the parameters , , and .

The NIG model assumes that the stochastic variance follows an inverse Gaussian distribution with parameters and , where

The following figure shows the density of NIG distribution with different parameters.

Parameter Estimation

- Ngme2 does maximum likelihood estimation through preconditioned stochastic gradient descent. See Model estimation and prediction for more details.

- Multiple chains are supported for better convergence checks.

- Different stochastic optimization algorithms can be used for the

optimization process. See

?ngme_optimizersfor more details. - Different convergence checks are supported.

Ngme Model Structure

Specify the driven noise

There are 2 types of common noise involved in the model, one is the

innovation noise of a stochastic process, one is the measurement noise

of the observations. They can be both specified by

noise_<type> function.

For now we support normal, skew_t, NIG, and GAL noises.

The R class ngme_noise has the following interface:

library(fmesher)

library(splancs)

library(lattice)

library(ggplot2)

library(grid)

library(gridExtra)

library(viridis)

library(ngme2)

noise_normal(sigma = 1) # normal noise

#> Noise type: NORMAL

#> Noise parameters:

#> sigma = 1

noise_nig(mu = 1, sigma = 2, nu = 1) # nig noise

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 1

#> sigma = 2

#> nu = 1

noise_nig( # non-stationary nig noise

B_mu = matrix(c(1:10), ncol = 2),

theta_mu = c(1, 2),

B_sigma = matrix(c(1:10), ncol = 2),

theta_sigma = c(1, 2),

nu = 1

)

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> theta_mu = 1, 2

#> theta_sigma = 1, 2

#> nu = 1

noise_skew_t(mu = 1, sigma = 2, nu = 1) # skew_t noise

#> Noise type: SKEW_T

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 1

#> sigma = 2

#> nu = 1 (lower bound 0.01)Notice that the 3rd example is defined for non-stationary NIG noise. In general, we can define non-stationary noise by the following: where , , and

ngme_noise(

type, # the type of noise

theta_mu, # mu parameter

theta_sigma, # sigma parameter

theta_nu, # nu parameter

B_mu, # basis matrix for non-stationary mu

B_sigma, # basis matrix for non-stationary sigma

B_nu # basis matrix for non-stationary nu

)It will construct the following noise structure:

Additionally, ngme2 provides a special combined noise

model that merges both Gaussian and NIG noise components:

noise_normal_nig(

mu = 2, # NIG parameter mu

sigma_nig = 3, # NIG noise scale

nu = 1, # NIG shape parameter

sigma_normal = 0.8 # Normal noise standard deviation

)

#> Noise type: NORMAL_NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 2

#> sigma_nig = 3

#> nu = 1

#> sigma_normal = 0.8This combined noise model is particularly useful for complex

processes where both normal variations and heavy-tailed events occur.

For more details, see the dedicated vignette:

vignette("normal-nig-noise", package = "ngme2").

Specify stochastic process with f function

The middle layer is the stochastic process, in R interface, it is

represented as a f function. The process can be specified

by different noise structure. See ?ngme_model_types() for

more details.

Some examples of using f function to specify

ngme_model:

f(1:10, model = ar1(), noise = noise_nig())

#> Model type: AR(1)

#> rho = 0

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 0

#> sigma = 1

#> nu = 1One useful model would be the SPDE model with Gaussian or non-Gaussian noise, see the vignette for details.

Specifying latent models with formula in ngme

The latent model can be specified additively as a

formula argument in ngme function together

with fixed effects.

We use R formula to specify the latent model. We can specify the

model using f within the formula.

For example, the following formula

formula <- Y ~ x1 + f(

x2,

model = ar1(),

noise = noise_nig()

) + f(x3,

model = rw1(),

noise = noise_normal()

)corresponds to the model

where

is an AR(1) process,

is a random walk 1 process.

is random effects.. . By default, we have intercept. The distribution of

the measurement error

is given in the ngme function.

The entire model can be fitted, along with the specification of the

distribution of the measurement error through the ngme

function:

ngme(

formula = formula,

family = noise_normal(sigma = 0.5),

data = data.frame(Y = 1:5, x1 = 2:6, x2 = 3:7, x3 = 4:8),

control_opt = control_opt(

estimation = FALSE

)

)

#> *** Ngme object ***

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> (Intercept) x1

#> -1 1

#>

#> Models:

#> $field1

#> Model type: AR(1)

#> rho = 0

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 0

#> sigma = 1

#> nu = 1

#>

#> $field2

#> Model type: Random walk (order 1)

#> No parameter.

#> Noise type: NORMAL

#> Noise parameters:

#> sigma = 1

#>

#> Measurement noise:

#> Noise type: NORMAL

#> Noise parameters:

#> sigma = 0.5It gives the ngme object, which has three parts:

- Fixed effects (intercept and x1)

- Measurement noise (normal noise)

- Latent models (contains 2 models, ar1 and rw1)

We can turn the estimation = TRUE to start estimating

the model.

Convergence check methods

ngme2 can monitor convergence with three optional

diagnostics. They all run at each checkpoint (every

iters_per_check iterations, default

iterations / n_batch). Checks only begin after

n_min_batch checkpoints have accumulated.

Gelman–Rubin R̂ (

R_hat_conv_check,max_R_hat)

Compares between- and within-chain variance for each parameter; pass ifR_hat <= max_R_hat(default 1.1). Requires at least 2 chains (n_parallel_chain >= 2).-

Trend/Std diagnostic (

trend_std_conv_check)

Uses the lastn_slope_checkcheckpoints (default 3). Passes when both hold for each parameter:-

sqrt(var) / |mean| <= std_lim(default 0.01)

- |linear slope over last

n_slope_checkmeans|<= trend_lim(default 0.01).

-

Pflug diagnostic (

pflug_conv_check,pflug_alpha)

For each chain, checkspflug_sum < pflug_alpha * max_pflug_sumin the latest batch (defaultpflug_alpha = 1). If all chains satisfy this, convergence is declared regardless of the other two checks.

Combination rule: - A parameter is considered converged if

any enabled diagnostic passes for it (R̂ or

Trend/Std).

- Overall convergence is reached when all parameters are converged, or

when the Pflug diagnostic passes for all chains.

Key control knobs (set via control_opt()):

ctrl <- control_opt(

n_batch = 10, # number of checkpoints

n_min_batch = 3, # don't check before this many checkpoints

n_slope_check = 3, # window for trend regression

R_hat_conv_check = TRUE,

max_R_hat = 1.1,

trend_std_conv_check = TRUE,

std_lim = 0.01,

trend_lim = 0.01,

pflug_conv_check = TRUE,

pflug_alpha = 1,

print_check_info = TRUE # print per-check diagnostics

)Recommendations: - Use at least two chains for R̂; with one chain only

Trend/Std and Pflug can run. - If checks trigger too early, increase

n_min_batch or loosen std_lim /

trend_lim. - Pflug is inexpensive; keep it on unless it

yields false positives in your model.

A simple example - AR1 process with nig noise

Now let’s see an example of an AR1 process with nig noise. The process is defined as

Here, is the iid NIG noise. And, it is easy to verify that , where

n_obs <- 500

sigma_eps <- 0.5

rho <- 0.5

mu <- 2

delta <- -mu

sigma <- 3

nu <- 1

# First we generate V. V_i follows inverse Gaussian distribution

trueV <- ngme2::rig(n_obs, nu, nu, seed = 10)

# Then generate the nig noise

mynoise <- delta + mu * trueV + sigma * sqrt(trueV) * rnorm(n_obs)

trueW <- Reduce(function(x, y) {

y + rho * x

}, mynoise, accumulate = T)

Y <- trueW + rnorm(n_obs, mean = 0, sd = sigma_eps)

# Add some fixed effects

x1 <- runif(n_obs)

x2 <- rexp(n_obs)

beta <- c(-3, -1, 2)

X <- (model.matrix(Y ~ x1 + x2)) # design matrix

Y <- as.numeric(Y + X %*% beta)Now let’s fit the model using ngme. Here we can use

control_opt to modify the control variables for the

ngme. See ?control_opt for more optioins.

# Fit the model with the AR1 model

fit_nig <- ngme(

Y ~ x1 + x2 + f(

1:n_obs,

name = "my_ar",

model = ar1(),

noise = noise_nig()

),

data = data.frame(x1 = x1, x2 = x2, Y = Y),

control_opt = control_opt(

burnin = 100,

iterations = 2000,

n_parallel_chain = 4,

seed = 3,

pflug_conv_check = TRUE,

pflug_alpha = 1

)

)

#> Starting estimation...

#>

#> Starting posterior sampling...

#> Posterior sampling done!

#> Average standard deviation of the posterior W: 4.332125

#> Note:

#> 1. Use ngme_post_samples(..) to access the posterior samples.

#> 2. Use ngme_result(..) to access different latent models.Next we can read the result directly from the object.

fit_nig

#> *** Ngme object ***

#>

#> Fixed effects:

#> (Intercept) x1 x2

#> -2.84 -1.36 2.03

#>

#> Models:

#> $my_ar

#> Model type: AR(1)

#> rho = 0.575

#> Noise type: NIG

#> Noise parameters:

#> mu = 1.9

#> sigma = 3

#> nu = 0.899

#>

#> Measurement noise:

#> Noise type: NORMAL

#> Noise parameters:

#> sigma = 0.539The estimation results are close to the real parameter.

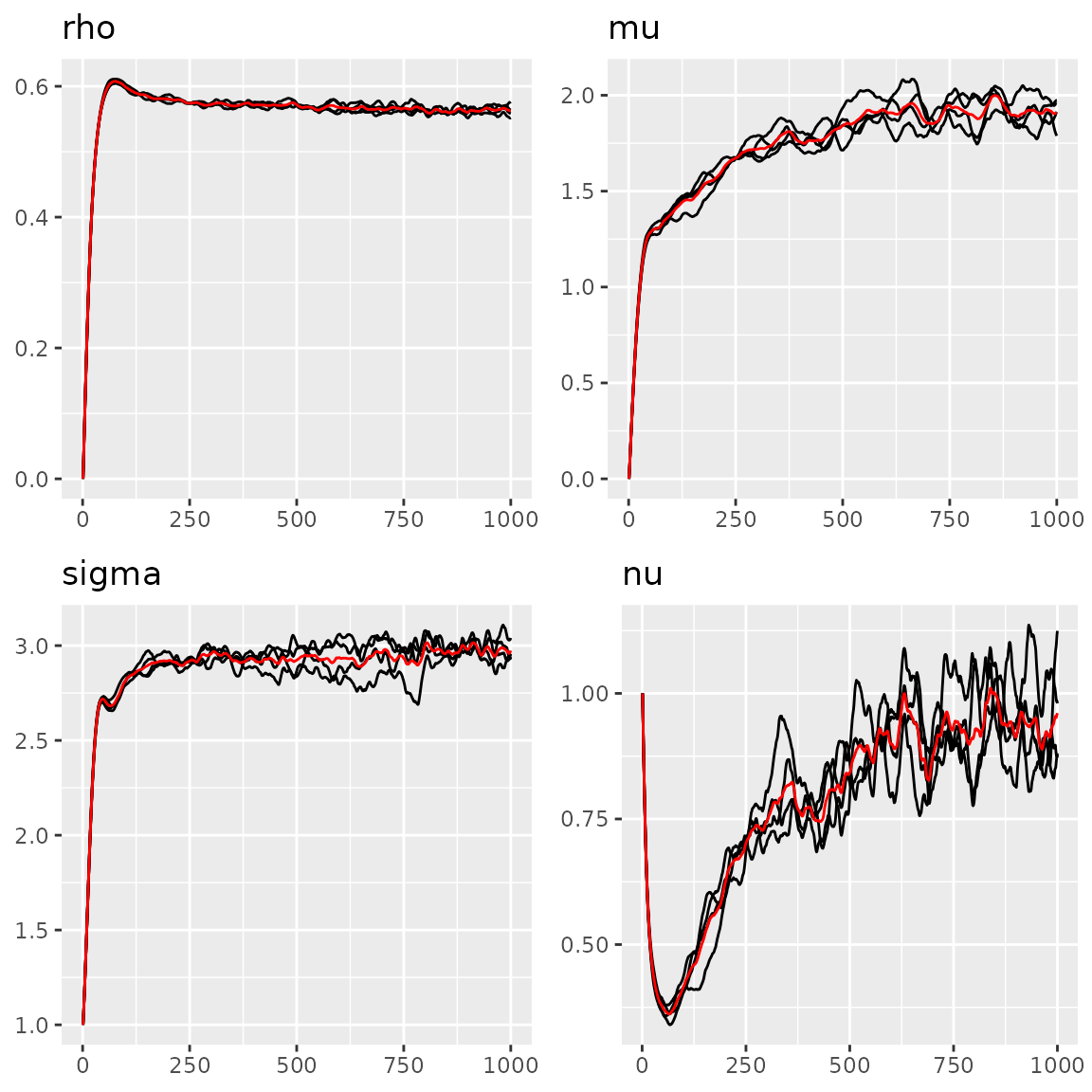

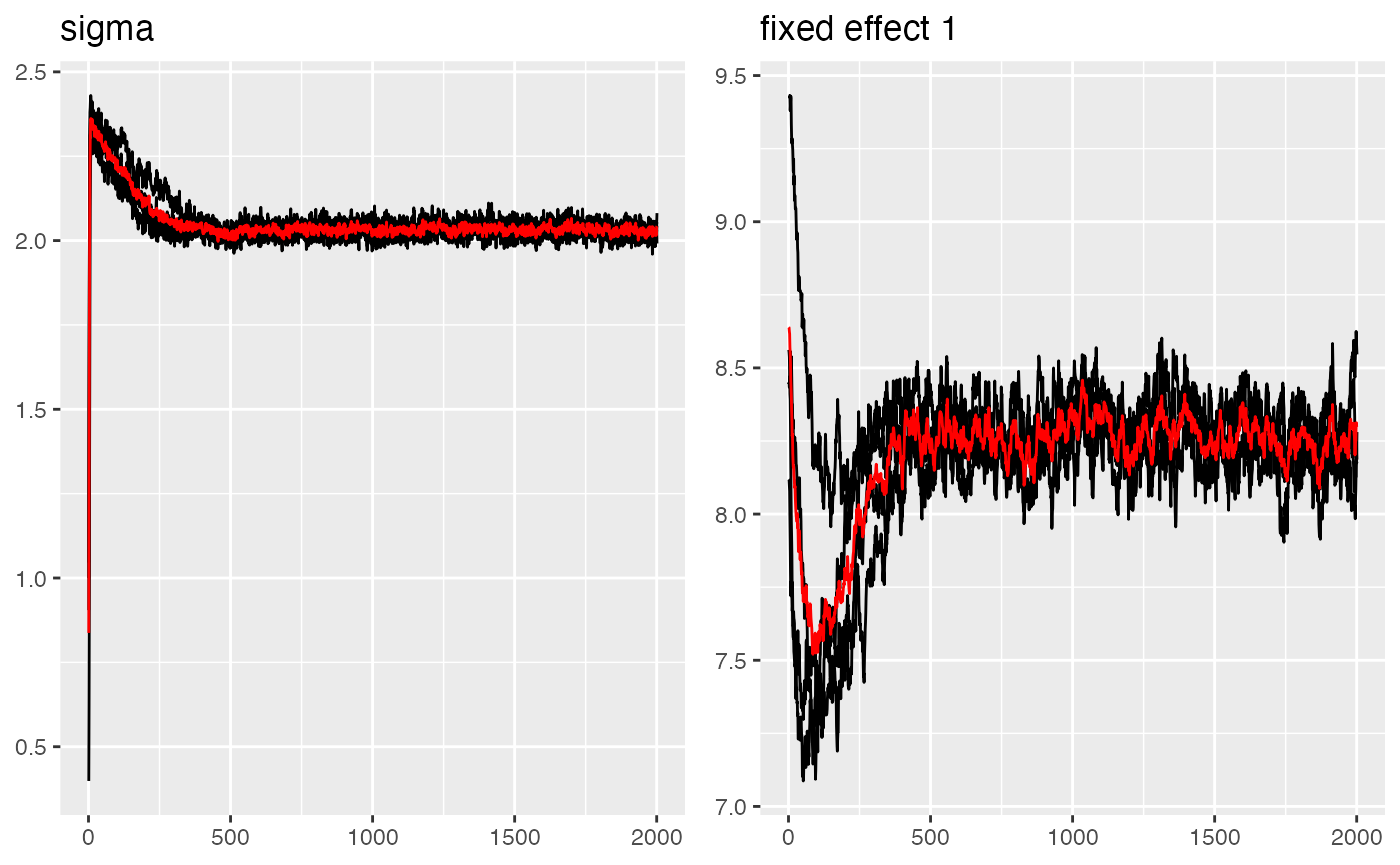

We can also use the traceplot function to see the

estimation traceplot.

Parameters of the AR1 model

#> Last estimates:

#> $rho

#> [1] 0.5751108

#>

#> $mu

#> [1] 1.768192

#>

#> $sigma

#> [1] 3.02051

#>

#> $nu

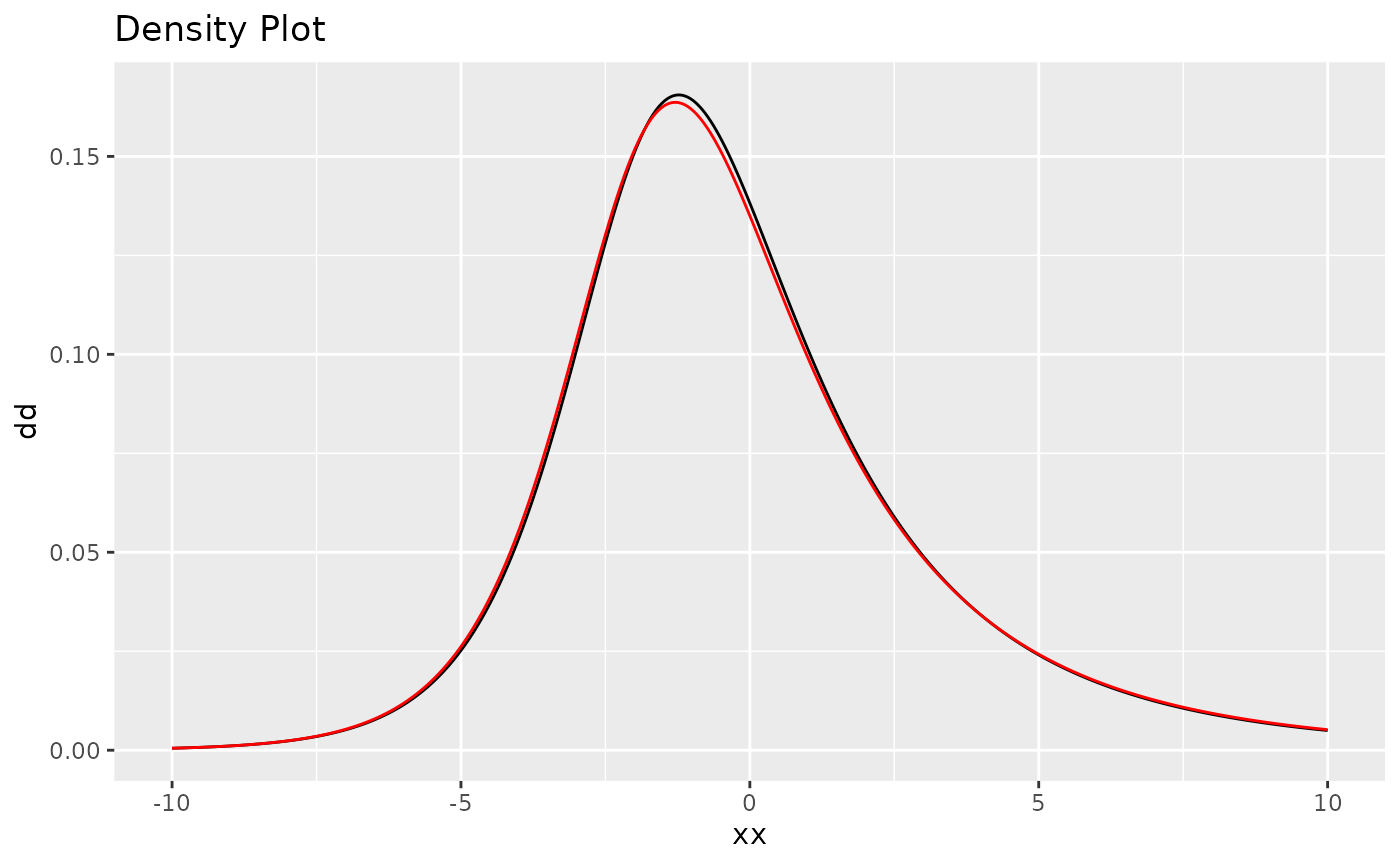

#> [1] 0.8840925We can also do a density comparison with the estimated noise and the true NIG noise, we can see they are very close:

# fit_nig$replicates[[1]] means for the 1st replicate

plot(

fit_nig$replicates[[1]]$models[[1]]$noise,

noise_nig(mu = mu, sigma = sigma, nu = nu)

)

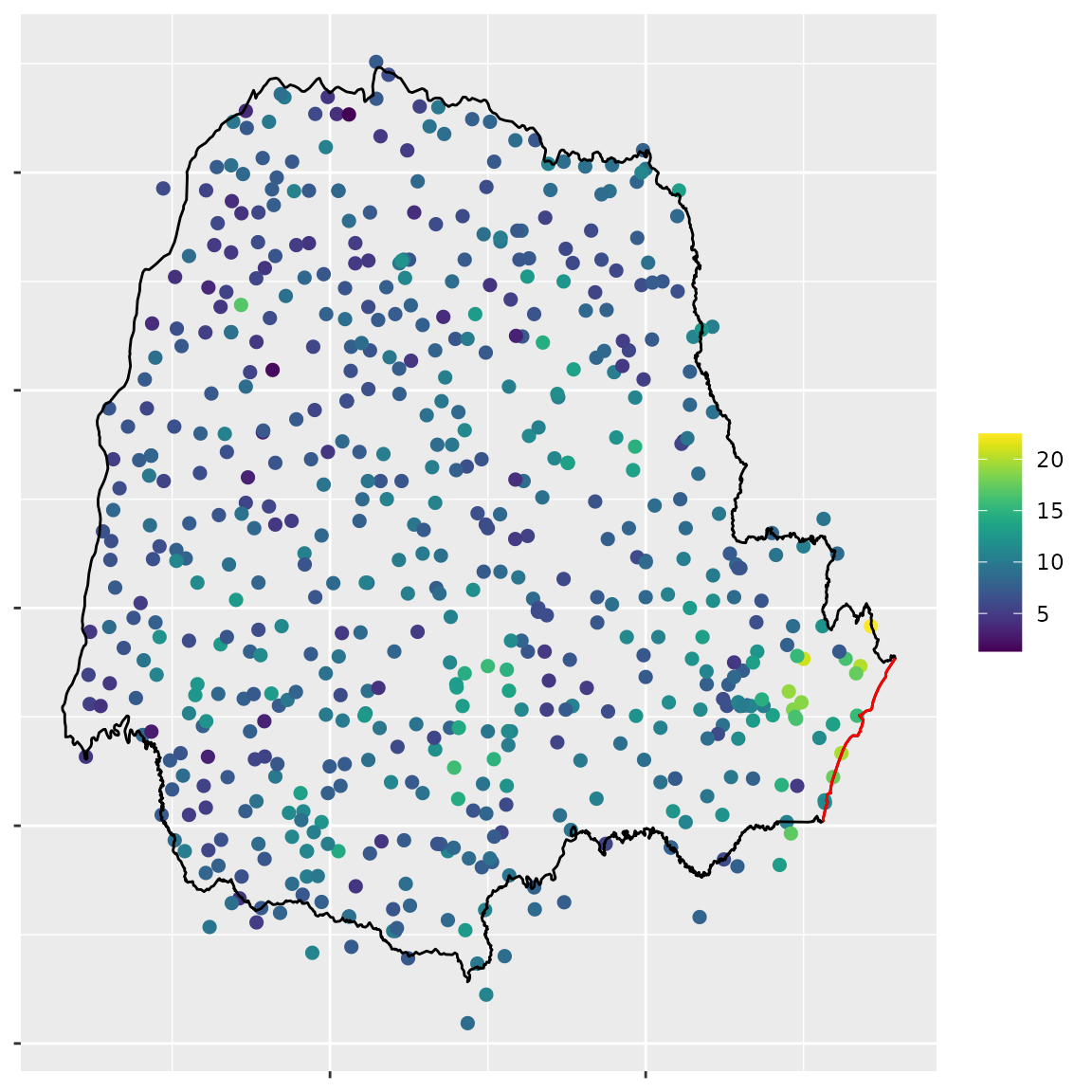

Paraná dataset

The rainfall data from Paraná (Brazil) is collected by the National Water Agency in Brazil (Agencia Nacional de Águas, ANA, in Portuguese). ANA collects data from many locations over Brazil, and all these data are freely available from the ANA website (http://www3.ana.gov.br/portal/ANA).

We will briefly illustrate the command we use, and the result of the estimation.

library(INLA)

#> Loading required package: Matrix

#> This is INLA_25.04.16 built 2025-04-16 08:17:54 UTC.

#> - See www.r-inla.org/contact-us for how to get help.

#> - List available models/likelihoods/etc with inla.list.models()

#> - Use inla.doc(<NAME>) to access documentation

#> - Consider upgrading R-INLA to testing[26.02.06] or stable[25.10.19] (require R-4.5)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'INLA'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:ngme2':

#>

#> f

data(PRprec)

data(PRborder)

# Create mesh

coords <- as.matrix(PRprec[, 1:2])

prdomain <- fmesher::fm_nonconvex_hull(coords, -0.03, -0.05, resolution = c(100, 100))

prmesh <- fmesher::fm_mesh_2d(boundary = prdomain, max.edge = c(0.45, 1), cutoff = 0.2)

# monthly mean at each location

Y <- rowMeans(PRprec[, 12 + 1:31]) # 2 + Octobor

ind <- !is.na(Y) # non-NA index

Y <- Y_mean <- Y[ind]

coords <- as.matrix(PRprec[ind, 1:2])

seaDist <- apply(spDists(coords, PRborder[1034:1078, ],

longlat = TRUE

), 1, min)Plot the data:

Mean of the rainfall in Octobor 2012 in Paraná

# Define the control options

control <- control_opt(

iterations = 2000,

n_min_batch = 4,

n_batch = 10,

n_parallel_chain = 4,

optimizer = precond_sgd(),

print_check_info = FALSE,

seed = 16

)

parana_fit <- ngme(

formula = Y ~ 1 +

f(coords,

model = matern(

mesh = prmesh,

),

noise = noise_nig(),

name = "spde"

),

data = data.frame(Y = Y),

family = "normal",

control_opt = control

)

#> Starting estimation...

#>

#> Starting posterior sampling...

#> Posterior sampling done!

#> Average standard deviation of the posterior W: 2.87084

#> Note:

#> 1. Use ngme_post_samples(..) to access the posterior samples.

#> 2. Use ngme_result(..) to access different latent models.

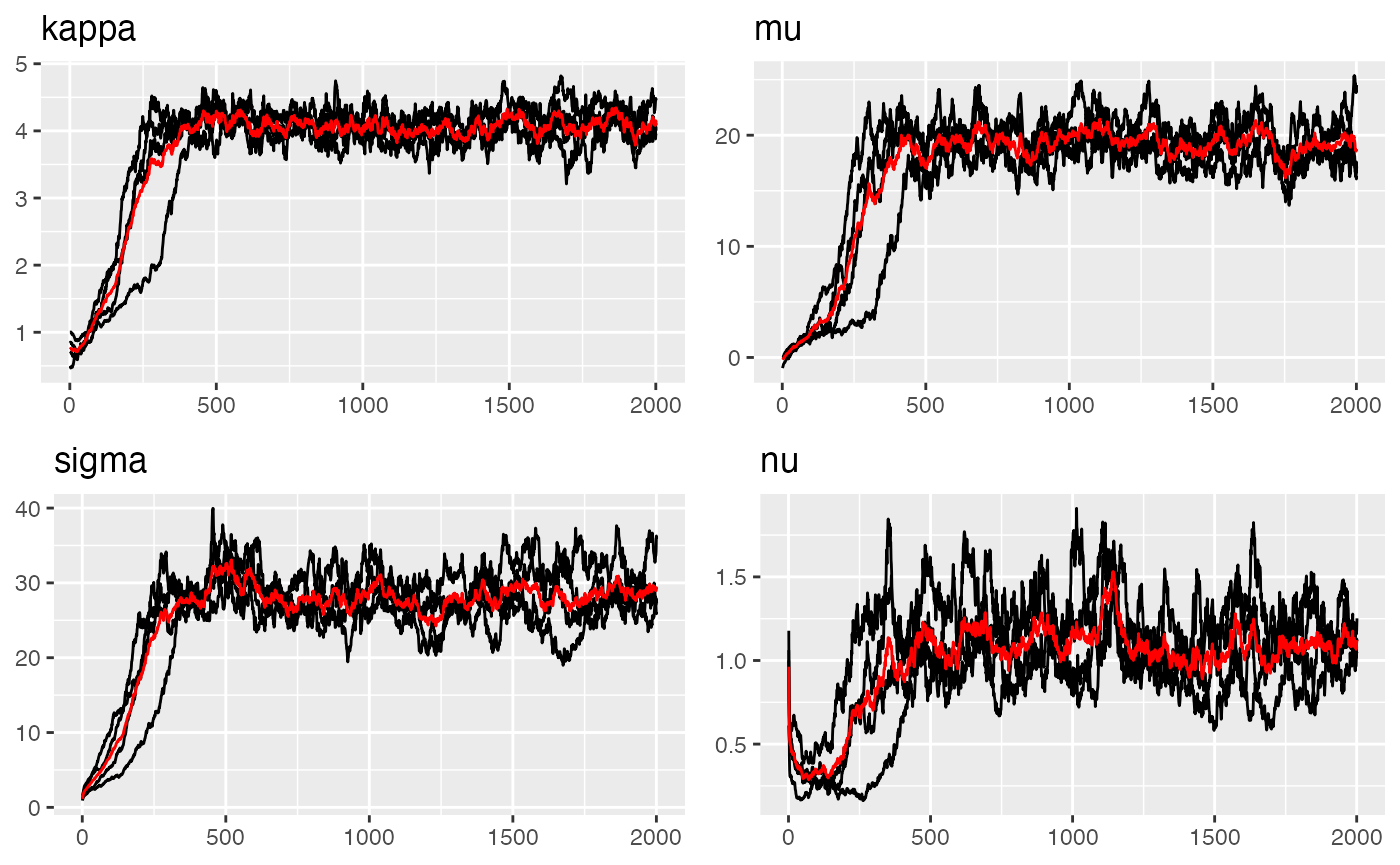

# traceplots

## fixed effects and measurement error

traceplot(parana_fit, "data")

#> Last estimates:

#> $sigma

#> [1] 2.042884

#>

#> $`(Intercept)`

#> [1] 8.297917

## spde model

traceplot(parana_fit, "spde")

#> Last estimates:

#> $kappa

#> [1] 4.124553

#>

#> $mu

#> [1] 18.75537

#>

#> $sigma

#> [1] 29.15408

#>

#> $nu

#> [1] 1.132146Parameter estimation results:

#> $beta

#> (Intercept)

#> 8.241518

#>

#> $sigma

#> [1] 2.027681

#> $kappa

#> [1] 4.100826

#>

#> $mu

#> [1] 19.20593

#>

#> $sigma

#> [1] 28.8247

#>

#> $nu

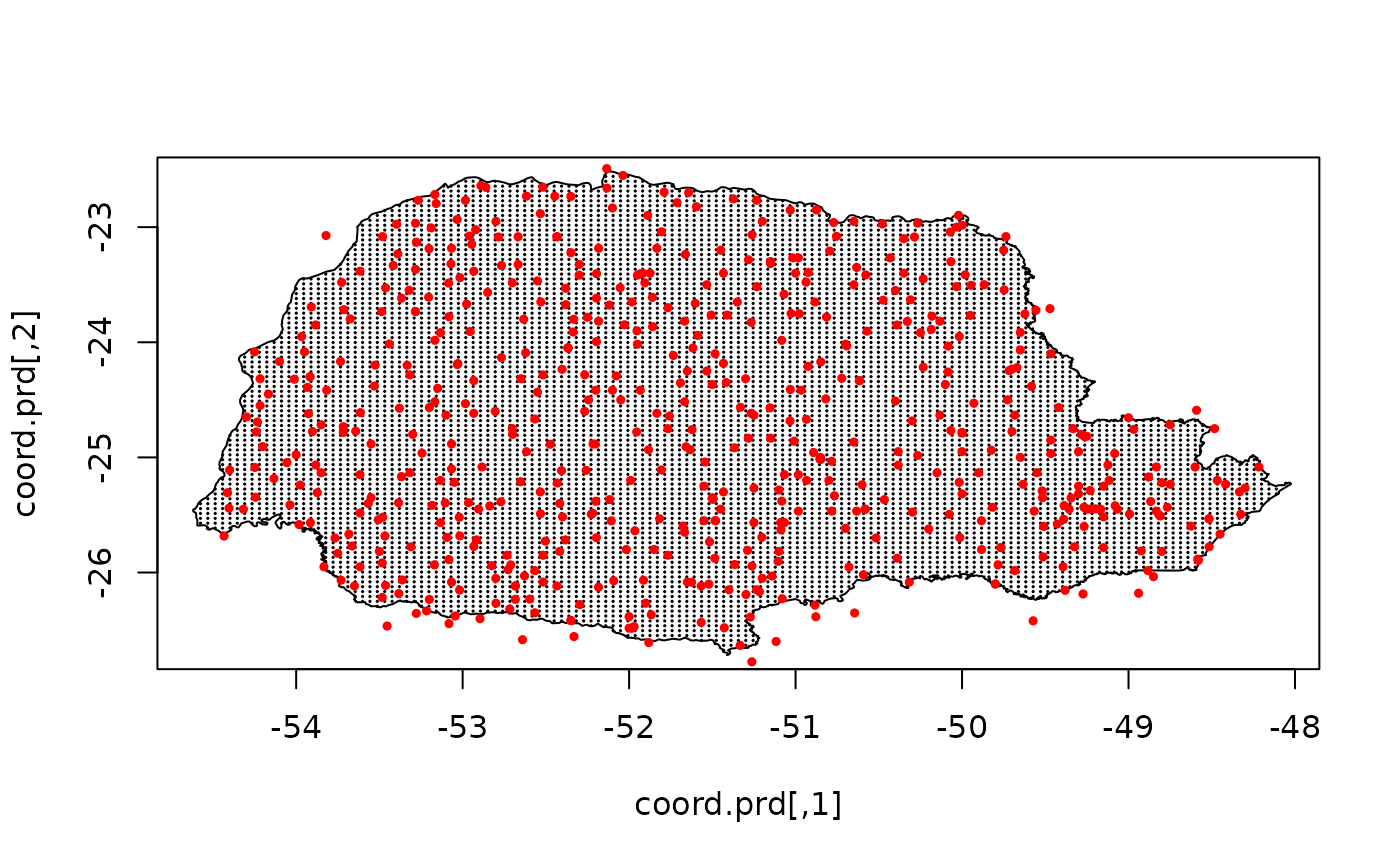

#> [1] 1.084761Prediction

Now we can use the fitted model to do prediction by generating the prediction grid and giving the predict location.

nxy <- c(150, 100)

projgrid <- rSPDE::rspde.mesh.projector(prmesh,

xlim = range(PRborder[, 1]),

ylim = range(PRborder[, 2]), dims = nxy

)

xy.in <- inout(projgrid$lattice$loc, cbind(PRborder[, 1], PRborder[, 2]))

coord.prd <- projgrid$lattice$loc[xy.in, ]

plot(coord.prd, type = "p", cex = 0.1)

lines(PRborder)

points(coords[, 1], coords[, 2], pch = 19, cex = 0.5, col = "red")

# Doing prediction by giving the predict location

pds <- predict(parana_fit, map = list(spde = coord.prd))

lp <- pds$mean

ggplot() +

geom_point(aes(

x = coord.prd[, 1], y = coord.prd[, 2],

colour = lp

), size = 2, alpha = 1) +

geom_point(aes(

x = coords[, 1], y = coords[, 2],

colour = Y_mean

), size = 2, alpha = 1) +

scale_color_gradientn(colours = viridis(100)) +

geom_path(aes(x = PRborder[, 1], y = PRborder[, 2])) +

geom_path(aes(x = PRborder[1034:1078, 1], y = PRborder[

1034:1078,

2

]), colour = "red")

Model comparison with latent Gaussian model via cross-validation

We can also fit a latent Gaussian model and compare it with the NIG model via cross-validation. The following code shows how to do it. For the details of the cross-validation, see the cross-validation vignette.

parana_fit_gauss <- ngme(

formula = Y ~ 1 +

f(coords,

model = matern(

mesh = prmesh,

),

noise = noise_normal(),

name = "spde"

),

data = data.frame(Y = Y),

family = "normal",

control_opt = control

)

#> Starting estimation...

#>

#> Starting posterior sampling...

#> Posterior sampling done!

#> Average standard deviation of the posterior W: 2.572308

#> Note:

#> 1. Use ngme_post_samples(..) to access the posterior samples.

#> 2. Use ngme_result(..) to access different latent models.

cv <- cross_validation(

list(

gauss = parana_fit_gauss,

nig = parana_fit

),

type = "k-fold",

seed = 13,

n_gibbs_samples = 2000,

n_burnin = 100,

k = 10,

print = FALSE

)

cv

#> $mean.scores

#> MAE MSE neg.CRPS neg.sCRPS

#> gauss 1.740767 5.230700 1.247329 1.457489

#> nig 1.730342 5.209617 1.244528 1.453643

#>

#> $sd.scores

#> MAE MSE neg.CRPS neg.sCRPS

#> gauss 0.002581289 0.01328677 0.003350892 0.001549784

#> nig 0.003524973 0.02285076 0.003478937 0.001643864As we can see, the NIG model has a slightly better cross-validation performance in most metrics.